Of our many hikes in the Southwestern United States, we both look back at one in awe—short, sweet and a palette of pinks—Lower Hackberry Canyon.

“There was something out there,” said Magellan.

Hackberry Canyon is remote. To reach it, you drive the “unimproved” Cottonwood Canyon Scenic Backway, renowned for having some of the most spectacular geology in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument (our favourite area in Utah).

We’d been following the Cottonwood Canyon Geology Road Guide, stopping frequently to see fossilized oysters, the “squeeze” and other geological features, so it was later in the afternoon when we arrived at Hackberry. Rove-Inn had the small parking lot to herself.

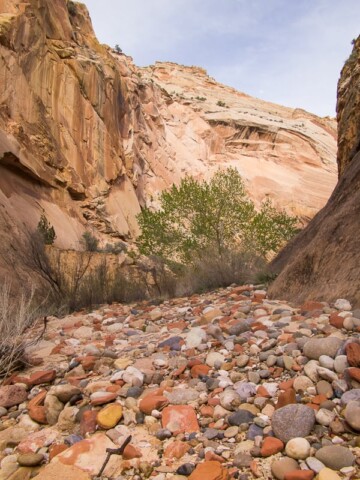

As we circled around a copse of willows to get to the trailhead, the colours astounded us. Hackberry’s sheer walls of Navajo sandstone rise from the narrow canyon—dressed from top to bottom in shades of geological pink. Desert primrose. Nude blush. Cameo coral. Deepening to Cockscomb vermilion, black cherry and dusky maroon. A thesaurus of pinks that begins in the canyon’s coral-pink bottom, the colour of salmon roe.

I suppose little fish could live here—Hackberry is a rivulet in the springtime and sometimes year-round, a streambed of cobbles and sand. Unique for a desert hike.

At first we stepped around shallow pools of quietly rippling water, hopscotching onto the sand bars. A few hundred metres down the walled-in canyon, I suggested we take off our hiking boots. “Okay, but let’s find a high rock shelf for them,” said Magellan.

Hackberry narrowly ribbons through the canyon. The hike has no particular endpoint, although our guidebook told us that most people turn around when the canyon widens. And explained that the rocks are 60 million to 200 million years old, the pinkest rocks (which get their colour from the red mineral, hematite) of the Chinle Formation are also the oldest…and a whole lot of other stuff that Magellan was interested in. I was watching for the historic inscription honouring the Chynoweth family, whose cattle hooves made tracks in the enclosed canyon until the 1950s. And I really wanted to see some very old tracks, those of the carnivorous Grallator dinosaurs that roamed here 190 million years ago. Grallators walked on two legs, using their small hands to grasp prey. Upstream, their three-toed tracks were supposed to be easy to spot.

It was early April. All alone in the canyon, the wild beauty rendered us speechless. Sure, Vancouver is a lush “green” oceanside city, and we live near three parks but it’s not Shakespeare’s definition of nature (chief nourisher of life’s feast)—my word for it would be nurbanity. National parks used to be nature’s tonic, but more and more in the public’s shared wilderness, conservation is being overrun by consumerism and contemplation has become a nostalgic memory.

What brings calm is space—being made to feel that we are but a tiny element in something far larger and more mysterious. Deserts know this point well.

That is the essence of Hackberry. Where the tracks of our bare feet imprinted in the rosy sand were the only signs of life.

Until.

“Look at these,” Magellan said, pointing to animal tracks in the sand near the canyon wall.

“How fresh do you think they are?” I questioned, looking at the clawed tracks headed in the same direction as us.

“Today’s,” said Magellan.

“Bobcat?” I pondered, “Or wolf? I don’t know my animal tracks but we have that sheet of paper from the BLM that describes them in Rove-Inn.”

We carried on.

Until we saw tracks coming toward us. Recently clawed into the damp sand by the canyon’s edge.

How fast can you say, “Let’s turn around?”

The only info we could find on wild animals in the Hackberry area came from the Southwestern Utah Wilderness Alliance. “Wolves and coyotes, the bane of the stockman, have been so reduced in numbers as to be no longer a serious menace…Mountain lion and mule deer inhabit the unit.”

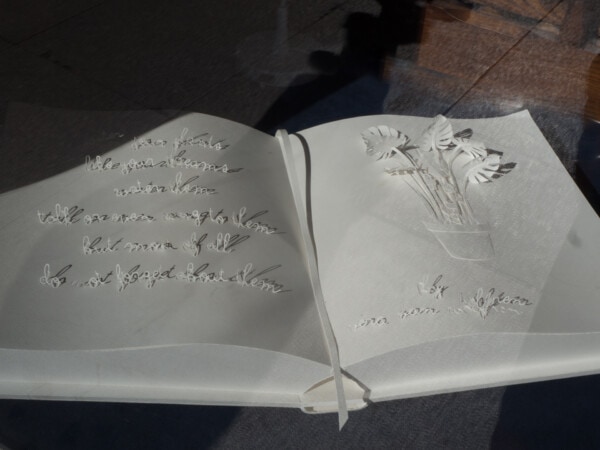

I may never see the ancient tracks of a Grallator. But something out there left recent tracks to wonder about, in a world where there is precious little wonder remaining, indelible tracks that still have us contemplating the joy of footprints in the pink sand, a feeling that’s much like the words of the children’s poet Shel Silverstein,

And all the colors I am inside

Have not been invented yet.

Navigation

The quote, “Love, maps, nature, and books are all we have to take us out of time…” is from Anne Lamott from her 2017 book Hallelujah Anyway: Rediscovering Mercy. “What brings calm is space—being made to feel that we are but a tiny element in something far larger and more mysterious. Deserts know this point well,” is from Alain de Botton at The Book of Life. Shel Silverstein’s quote is from his book Where the Sidewalk Ends, first published in 1975.

Gillespie, Janice. Geology Road Guide Cottonwood Canyon. Page, Arizona: Glen Canyon Natural HIstory Association, 2014. We highly recommend the 46-mile Cottonwood Canyon Scenic Backway through Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. From the booklet: “The backway provides access to Kodachrome Basin State Park, Grosvenor Arch, the Cottonwood Narrows, and Hackberry Canyon. Grosvenor Arch, located about 10 miles south of Kodachrome Basin and 1 mile east of the backway on a side road, is a superb double arch named in honor of a former National Geographic Society president. A bit less than 5 miles south of the turnoff to Grosvenor Arch is a parking area for accessing the Cottonwood Narrows, an easy 3-mile round-trip hike. Eight miles farther south on the backway is the trailhead for Lower Hackberry Canyon, a moderately easy in-and-out day hike along the canyon floor with gently flowing water, or a moderately difficult route for several days of backpacking depending on how far into the canyon one goes.”

Lower Hackberry Canyon gets its name from a large deciduous tree in the cannabaceae family that’s common in the area. It’s also known as a nettle tree, sugarberry and beaverwood. It has a light brown to yellowish-grey wood with yellow streaks, grows 10-25 metres high and produces a fruit-like date. Luckily, Lower Hackberry survived the severe cuts (land area reduced by half) that the Trump government made to Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

5 Responses

What brings calm is space, Perfect.

I do not think you are looking at Lynx tracks as normally you do not see the toe nail on lynx tracks as the foot is quite large and provides additional flotation.

Depending on size of the tracks they can be Fox or Coyote, the later more likely as they are very common in all areas including the suburbs. We see all three on our property in Saskatchewan and our people cams pick them up at a minimum of weekly, the cats not often at all maybe every 6 months and usually in winter. Wolf tracks can be bigger than your hand but that will depend on sex, age and overall health of the animal. We live on sand so tracks are very easy to detect and great for doing casts using drywall spackle or left over cement from projects.

Love the area you are hiking in, very awesome. Great way to cool the feet.

Cheers and happy ❤️ Day.

Thanks Barry, Margie and Diane.

The heel of my boot is 8 cm wide, similar in width to the track. Likely larger than a coyote, but maybe just a dog? We didn’t see anybody, but there could have been other hikers with their dog while we were farther up the canyon.

Lynx I think.

A short poem.

(I had to use 15 characters-lol)

Fox tracks….? Or wolf?

Could be? Too big for a coyote but a similar paw print.